As doctors always keep their knives and instruments at hand to deal with urgent cases, so you too should keep your doctrines at the ready, to enable you to understand things divine and human, and so to perform every action, even the very smallest, as one who is mindful of the bond that unites the two realms; for you will never act well in any of your dealings with the human unless you refer it to the divine, and conversely in your dealings with the divine. (Meditations 3.13)

Within the Stoic texts, we find many powerful passages with life-changing potential. Typically, these passages touch upon and draw together several key concepts and practices. This passage from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius is one of those; it highlights two concepts and one practice that is essential and potentially transformative for Stoics. The two concepts include the medical metaphor for Stoic practice and the relationship between things divine and human. The one practice Marcus refers to involves keeping essential Stoic doctrines “at the ready.” Together, these provide the Stoic practitioner with powerful tools to aid their Stoic way of life.

Philosophical Surgery: Therapy for the Soul

The first concept is highlighted by Marcus’ use of the medical metaphor to stress the fact that Stoic practice is a form of therapy for our soul (psyche). Epictetus also uses this medical metaphor when he reminds us that,

A philosopher’s school, man, is a doctor’s surgery. You shouldn’t leave after having had an enjoyable time, but after having been subjected to pain. For you weren’t in good health when you came in; no, one of you had a dislocated shoulder, another an abscess, another a headache. (Discourses 3.23.30)

Similarly, Seneca counseled Lucilius against traveling to ease his troubled mind. Instead, he argued that Lucilius needed a cure.

A sick person does not need a place; he needs medical treatment. If someone has broken a leg or dislocated a joint, he doesn’t get on a carriage or a ship; he calls a doctor to set the fracture or relocate the limb. Do you get the point? When the mind has been broken and sprained in so many places, do you think it can be restored by changing places? (Letters 104.17-18)

Stoicism is therapy for the soul; its holistic system and way of life were created to transform the thoughts and actions of a person and direct them toward virtue. Therefore, unlike all of the “success” formulas of modern times, Stoicism is designed to achieve well-being (eudaimonia) through the development of an excellence character. According to the Stoics, moral excellence (virtue), not wealth, health, reputation, of office, is what leads to well-being. As Epictetus points out, this process is not painless. People come to Stoicism with troubled minds, characters that are far from excellent, and lives that are wholly lacking in well-being. We come to Stoicism for the same reason we go to a surgeon; we are in immediate need of help, and we are willing to endure the pain of surgery to experience well-being. Do not be fooled by the three easy steps or life-hack approach to Stoic practice. Certainly, those methods can help; however, keeping with the medical metaphor, they are analgesic balms rather than a cure. These quick fixes may provide temporary relief; however, they cannot change your character to the extent necessary to experience true well-being. Well-being requires a character that is immune to the vicissitudes of life; therefore, it takes time to develop, and it requires constant practice. That is the reason Marcus reminds himself to keep the essential Stoic doctrines “at the ready” to deal with the events of life as they occur.

Keeping Stoic Doctrines at the Ready

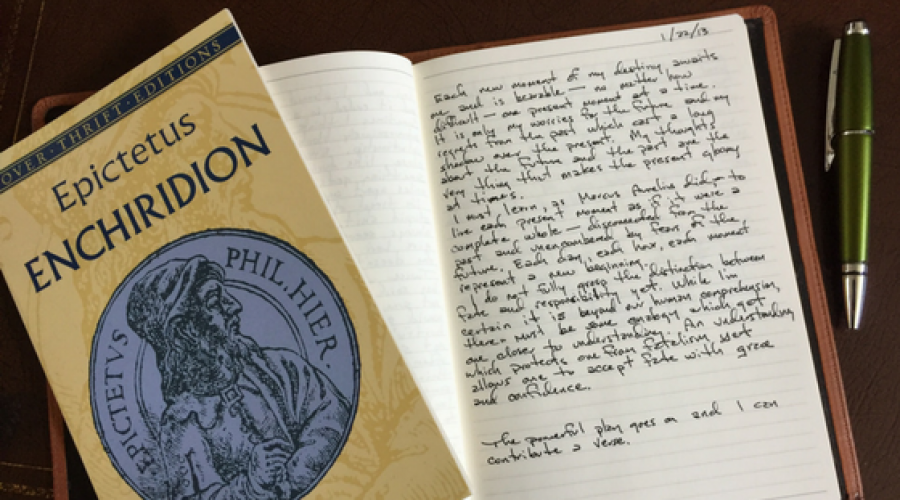

Keeping doctrines “at the ready” means memorizing them and contemplating them regularly. Marcus did just that in his journal to himself—the book we know as his Meditations. Marcus’ Meditations appear repetitive because it is. Marcus repeatedly contemplates the same Stoic doctrines from different angles and through different circumstances. He kept these at the readt by journaling. If you do not already engage in journaling, I highly recommend it. Try this each morning for a while. First, read from your Stoic text of choice; use an original text rather than a commentary. Read until something jumps off the page at you. This will likely be a passage that is relevant to some event or circumstance in your life. If nothing jump off the page at you, simply pick a passage you find interesting. Next, contemplate the passage for a few moments and then read it again. Now, pick up your pen and start journaling. Act as your own mentor and ask yourself the hard questions about applying the passage to your life. Journaling can serve as a powerful change agent if you do it consistently. Moreover, a year or two from now, you can review what you wrote and hopefully see the growth that came about as a result of your Stoic practice. Memorizing and journaling will help you keep Stoic doctrines “ready at hand.”

One of the most important Stoic doctrines to keep “at the ready” is also one that helps us “understand things human and divine.” That is the Dichotomy of Control (DOC). The whole point of the DOC is to distinguish properly between those things and events that are in our complete control (proairetic) and those we must trust to providence because they are not within our complete control (aproairetic). This doctrine, if kept “at the ready” and practiced consistently, can do more to transform your life than any other. Properly judging between what is in our complete control and what is not, and acting accordingly is what separates an unhindered life, free of harm, blame, and anger, from a hindered life, with its troubled and lamenting mind that blames gods and other humans (Enchiridion 1). If you are new to the practice of Stoicism, or your practice is stuck, I strongly recommend reading, contemplating, and journaling on two passages from the Enchiridion (Handbook) of Epictetus for a least a week to make them “at the ready.” The first passage is Enchiridion 1. The chart below outlines Epictetus’ Dichotomy of Control and shows where each path leads.

The second passage that is important to keep “at the ready” is Enchiridion 53. Epictetus opens this passage with the words that Marcus may have been referring to when he reminds himself to keep essential doctrines “at the ready.” Epictetus teaches us that “on every occasion” we should have the arguments of Enchiridion 53 “at hand.” I strongly encourage all practicing Stoics to memorize this passage, it reads:

Guide me, O Zeus, and thou, O Destiny,

To wheresoever you have assigned me;

I’ll follow unwaveringly, or if my will fails,

Base though I be, I’ll follow nonetheless

Whoever rightly yields to necessity

We accord wise and learned in things divine

Then Epictetus closes Enchiridion 53 with two quotes from Socrates, the patron saint of the Stoics. These quotes highlight the Dichotomy of Control and demonstrate that its heritage extends back to Socrates.

‘Well, Crito, if that is what is pleasing to the gods, so be it.’

‘Anytus and Meletus can kill me, but they cannot harm me.’

Arrian, the author of Epictetus’ Discourses and Enchiridion, was a student of Epictetus. He claimed the Discourses accurately represent Epictetus’ lectures. Arrian created the Enchiridion as a distillation to help students keep essential Stoic doctrines ready at hand. Interestingly, the Greek word ἐγχειριδιον (Enchiridion), means to have a small weapon (dagger or hand-knife) ready for use. Therefore, the Enchiridion was designed to be kept at the ready, for immediate use as we face the things and events in our lives. It is no accident that the Enchiridion opens and closes with the Dichotomy of Control. Stoic theory and practice revolve around this fundamental concept and its practice. The DOC is simultaneously the simplest doctrine to understand and the most difficult to live consistently. It touches on the Disciplines of Assent, Desire, and Action in ways that cut to the core of our character. Read it, meditate on it, journal about it, and return to it frequently; it has the power to transform your life. Keep it at the ready.

Natures: Divine and Human

The second concept Marcus highlights in Meditations 3.13 is the relationship between the human and the divine in Stoic practice. Marcus expresses his goal “to understand things divine and human” and suggests that is the reason to keep Stoic doctrines “at the ready.” Some moderns attempt to ignore this relationship between the divine and the human in Stoicism by arguing the famous Stoic edict to “live in agreement with nature” means to live according to human nature (reason) alone. While human reason is certainly necessary to live in agreement with nature, it is not sufficient for the development of the excellent character the Stoics have in mind. Chrysippus articulated the Stoic goal as:

Life in accordance with nature, or, in other words, in accordance with our own human nature as well as that of the universe. (Diogenes Laertius 7.87).

The additional phrase added by Chrysippus makes it clear the Stoics intended their famous doctrine to mean more than living in accordance with our rational human nature. This becomes clear when we consider the fact that human reason is a goal-directed, discursive process that can be aimed with equal success at things within our control and thing not within our control.[1] In other words, human reason can be aimed at either virtue or vice. Our human proairesis (the rational faculty capable of choice) is not infallible. In fact, most people mistakenly judge things and events to be in their control when they are not, or not within their control when they are. Therefore, human reason must be oriented toward an objective, normative standard to be virtuous and lead toward well-being. For the Stoics, that standard is Nature, which the Stoics considered divine, providential, and the source of our cosmic purpose. Australian philosopher Tim Mulgan relies on arguments remarkably similar to those of the Stoics in his recent book Purpose in the Universe. Like the Stoics, he claims that some form of cosmic purpose is necessary to establish objective moral values. He writes:

If a connection to the natural world is intrinsically valuable, then human lives go better (and perhaps can only go well) when they instantiate that value. Some things matter, and it matters that people are connected to real values, not virtual ones.[2]

This is essentially the same argument the Stoic offered. The cosmos has a purpose (teleology), and humans can only live well when the align themselves with that purpose—live in agreement with Nature. Mulgan continues:

My objectivist and externalist substantive claims are necessary components of any adequate intergenerational morality; that such a morality will strike human beings as very austere and demanding; and that only metaphysically robust moral realism can give us the motivation to follow such a demanding morality.[3]

Mulgan is arguing for an essential connection between metaphysics (a model of the world) and ethics (a model for the world) just as the Stoics did. He is arguing for a connection between physics and ethics. As the opening quote from Meditations 3.13 highlights, Marcus thought it was essential “to understand things divine and human.” We see this same phrase in Meditations 3.1 where Marcus refers to striving after “knowledge of things divine and human.” As the ancient Sceptic philosopher Sextus Empiricus points out, this connection was common among the dogmatic philosophers he opposed. He wrote:

The doctrine concerning Gods certainly seems to the Dogmatic philosophers to be most necessary. Hence they assert that “philosophy is the practice of wisdom, and wisdom is the knowledge of things divine and human.” (Against the Physicists I, 13)

Likewise, the ancient eclectic philosopher Aetius wrote:

The Stoics said that wisdom is scientific knowledge of the divine and the human, and that philosophy is the practice of expertise in utility. Virtue singly and at its highest is utility, and virtues, at their most generic, are triple – the physical one, the ethical one, and the logical one. For this reason philosophy also has three parts – physics, ethics and logic. Physics is practised whenever we investigate the world and its contents, ethics is our engagement with human life, and logic our engagement with discourse, which they also call dialectic. (Aetius 1, Preface; LS 26A)

Finally, in the continuation Letter 104 to Lucilius, Seneca also ties the relationship between thing divine and human to the Stoic practice of keeping essential doctrines close at hand.

If you really want to be rid of your vices, you must stay away from the patterns of those vices. If a miser, or seducer, or sadist, or cheat were close to you, they would do you a lot of harm— but in fact, these are already inside you! Make a conversion to better models. Live with either of the Catos, or with Laelius, or Tubero; or, if you prefer to cohabit with Greeks, spend your time with Socrates or Zeno. The former will teach you, if it is necessary, how to die; the latter, how to die before it is necessary. Live with Chrysippus or Posidonius. They will educate you in the knowledge of things human and divine; they will tell you to work not so much at speaking charmingly and captivating an audience with your words but at toughening your mind and hardening it in the face of challenges.” (Letters 104.21.22)

Seneca is instructing Lucilius to turn to Chrysippus and Posidonius for “knowledge of things human and divine” that will toughen his mind for the challenges of life. This is what Marcus is referring to in Meditations 3.13 when he reminds himself to: “keep your doctrines at the ready, to enable you to understand things divine and human, and so to perform every action, even the very smallest, as one who is mindful of the bond that unites the two realms…” This passage is worthy of serious contemplation. Marcus makes a clear and unambiguous connection between knowledge of things divine and human (physics—psychology and theology) and our ability to “perform every action” “mindful of the of the bond that unites the two realms”—divine and human. As Christopher Gill, professor of Ancient Thought at Exeter University, points out, “This formulation suggests the stress on the interface between ethics and physics (the study of nature) which is a distinctively Stoic feature; theology is seen as the culminating subject within physics.”[4]

For Marcus, the “bond that unites” the divine and the human is the daemon within us. The daemon is a fragment of the divine; what Seneca called the “sacred spirit” that dwells within us (Letters 41.1-2). This language does not entail anything supernatural, a ghost in the machine, or any form of Cartesian dualism. In Stoicism, everything that exists, down to smallest ontological entity, is comprised of a mixture of two principles (one active and one passive). The active principle is also called pneuma, and it exists in different configurations within the scale of nature from inanimate matter to human consciousness. The Stoics thought the rational faculty (hegemonikon) of humans was the most complex configuration of pneuma, and they considered it a fragment of the divine. This fragment of the divine is our daemon, sacred spirit, or God within. It is the connection between human reason and Universal Reason (aka Logos or God). Marcus’ “steady intimacy with the daemon within”[5] is on constant display throughout the Meditations, as he focusses on his relationship with the cosmos as a whole. Likewise, Epictetus lectured one of his students on the God within while addressing the essence of the good:

You for your part are of primary value; you’re a fragment of God. Why are you ignorant, then, of your high birth? Why is it that you don’t know where you came from?… You carry God around with you, poor wretch, and yet have no knowledge of it. Do you suppose that I mean some external god of gold or silver? It is within yourself that you carry him, and you fail to realize that you’re defiling him through your impure thoughts and unclean actions. (Discourses 2.8.11-13)

Take some time to consider your relationship with the divine in your Stoic practice. This does not entail any mystical beliefs or religious ceremonies. As Stoic scholar A.A. Long points out:

Conformity to God and imitation of God are expressions that [Epictetus] uses in characterizing human excellence; for God is the paradigm of the virtues human beings are equipped to achieve.[6]

One way our human relationship with the divine can be understood and enhanced is through the consistent practice to the Dichotomy of Control. By keeping the DOC at the ready for the things and events we face in life, we are acknowledging the limits of our human control and our trust in providence for that which we cannot control. This practice may require you to peel your clenched fingers off a few things you desire to control, and that may be uncomfortable, even painful at first. However, as Epictetus reminds us, therapy of the soul is like a doctor’s surgery; we should not expect it to be enjoyable. In fact, if your current Stoic practice is comfortable and pleasant, you may be doing something wrong. The path toward an excellent character and well-being will be necessarily painful in places because you were not in good psychological health when you embarked on it. Keep Stoic doctrines at the ready, control what is ‘up to us,’ and trust the outcome to providence. That is what it means to follow the Stoic path.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Scalenghe, Franco. “About the Arithmetic and the Geometry of Human Proairesis and the Natural Asymmetry by Which Unhappiness Wins the Game Against Happiness 3 to 1.” International Journal of Philosophy 3, no. 6 (January 9, 2016): 72–82. doi:10.11648/j.ijp.20150306.14. p.76

[2] Mulgan, Tim. Purpose in the Universe: The Moral and Metaphysical Case for Ananthropocentric Purposivism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. p. 23

[3] Ibid, p. 26

[4] Gill, Christopher. Marcus Aurelius Meditations, Books 1-6. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. P. 114

[5] Dragona-Monachou, Myrto. The Stoic Arguments for the Existence and the Providence of the Gods. Athens: National and Capodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of Arts, 1976. p. 261

[6] Long, A. A. Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. P. 144-5