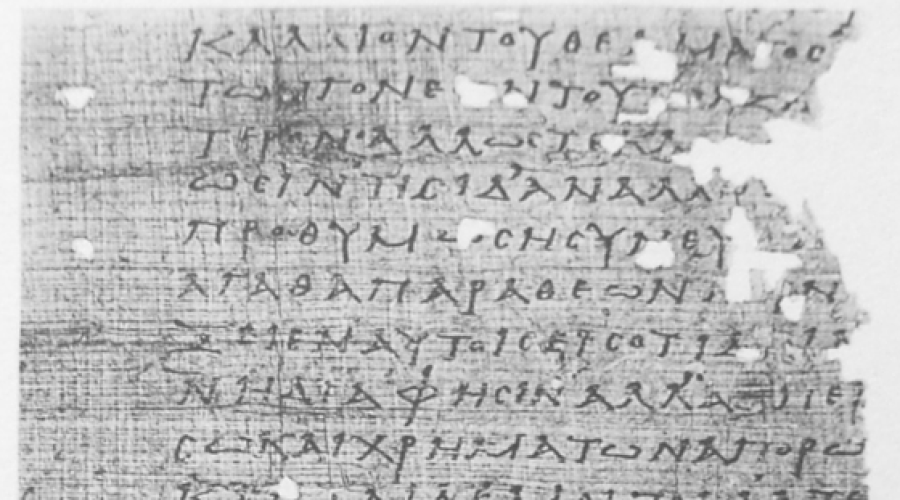

Musonius in situ

Of all the Stoics whose teachings survive, it’s fair to say that Musonius Rufus is the least studied, and I would argue, the least appreciated. For the past year I have been mostly a student solely of Musonius. When Chris started his series on The Piety of the Stoics, I asked if he had one planned for Musonius, and he suggested I try my hand at it. This is the result of that. I’d like to start off by thanking Chris and “Traditional Stoicism” for the opportunity to share some of what I’ve come to appreciate about the Roman Socrates.

“Of the things that exist, God has put some in our control, others not in our control. In our control he has put the noblest and most excellent part by reason of which He is Himself happy, the power of using our impressions. For when this is correctly used, it means serenity, cheerfulness, constancy; it also means justice and law and self-control and virtue as a whole. But all other things He has not put in our control. Therefore we ought to become of like mind with God and, dividing things in like manner, we ought in every way to lay claim to the things that are in our control, but what is not in our control we ought to entrust to the universe and gladly yield to it whether it asks for our children, our country, our body, or anything whatsoever.” — Musonius, Fragment 38[1]

Musonius was a contemporary of Epictetus, who was his student, and also of Seneca. He was exiled twice, sued for and received the conviction of Celer, who was instrumental in the unjust execution of Soranus (one of the Stoic Martyrs) under Nero[2], and above all practiced what he preached. Musonius’ teachings bend decidedly to the practical, he lays out an extensive ascetic regimen designed to help inculcate the ability to determine between apparent goods and evils, and true goods and evils. It will be no surprise, then, to the reader that his theology seems to take a similar practical bend. The above quote reminds one easily of Epictetus Enchiridion 1, yet, with a surprisingly even more religious content than Epictetus uses. This is worth nothing, as Epictetus is often renowned as having the most religious character to his works of the Roman Stoics.

“The cosmos is administered by mind and providence,”[3] is probably the most succinct distillation of Stoic theology which exists. The ‘god’ of Stoicism is and was quite different from the Greek Polytheism of the average Hellene. It does seem to be an interesting mixture of pantheism, deism, with touches of (ed: soft?) polytheism.[4]

Musonius and Sin

Musonius stands apart, as he often does. In fact, it has even been alleged that he was a Cynic rather than a Stoic.[5] Despite that, the common understanding is that Musonius is firmly in the Stoic camp, even when some of his teachings seem to be outliers. While the general conception of Stoic theology is metaphorical reinterpretations of Greek polytheist tradition to philosophical purposes, the language of Musonius’ lectures is more concrete.

“How can we help committing a sin against the gods of our fathers and against Zeus, guardian of the race, if we do this? For just as the man who is unjust to strangers sins against Zeus, god of hospitality, and one who is unjust to friends sins against Zeus, god of friendship, so whoever is unjust to his own family sins against the gods of his fathers and against Zeus, guardian of the family, from whom wrongs done to the family are not hidden, and surely one who sins against the gods is impious.” — Musonius, Lecture 15.2

In the original Koine Greek, there are two operative phrases which stand out: the word ἐξαμαρτάνοιμεν “we commit a grievous sin against” and the verb ἁμαρτάνει “to sin.”[6] It is common for us to read in the classical Stoics that unvirtuous action is ἀσεβής “impious”, but words and phrases like ‘grievously sin against’ are fairly rare.

Our recordings of Musonius’ teachings come from Stobaeus, in the fifth century through his students, Lucius and Epictetus (through Arian). Some of these latter translations may be tailored to make the pieces more palatable to a Christian audience, but it’s common practice to take the texts at face value, and believe the recorded quotation are accurate. This is especially the case when we see quoted sections verbatim, as is common for Chrysippus, for instance, in Stobaeus. Stobaeus reportedly had copies of original manuscripts, so the words may be accurate, and the connotations may have changed.

In a discussion with my Koine Greek expert of choice, Greg Wasson, he told me that the above words may have their etymological history in archery, and relate to “missing the mark” in regards to a thing, or target. These particular words are old, and have relationships that go back to Homer. The word ‘sin’ has a lot baggage from the Judeo-Christian heritage of the West, and not all of that may be appropriate to the pre-Christian philosophers we Stoics are interested in. Yet, the most common way you see these words translated into English is via the word ‘sin.’ Whether it’s “sin as we’d understand it” or ‘missing the mark of virtue’ does not change the fact that the rule and guide of Musonius’ measure is God.

Indeed, our godly nature due to reason implies an obligation and heritage which extends beyond that of other creatures. In fact, it’s the primary and most distinguishing thing about us:

“[F]or we do not study philosophy with our hands or feet or any other part of the body, but with the soul and with a very small part of it, that which we may call the reason. This God placed in the strongest place so that it might be inaccessible to sight and touch, free from all compulsion and in its own power.” — Musonius, Lecture 16.10

Praxis

One of the things which bears remarking upon is how Musonius divides up the types of trainings which are appropriate for philosophers. Epictetus notes in Book III, Chapter XII of the Discourses that,

“We ought not to train ourselves in unnatural or extraordinary actions, for in that case we who claim to be philosophers shall be no better than mountebanks. For it is difficult to walk on a tight-rope, and not only difficult but dangerous as well…”

From this, we can infer that Musonius would have held a similar perspective, as noted in the regimen he prescribed in his Lectures. We may even go so far as to argue that wanton damaging of the self might be impious, which would remain separate from the noble suicide of the Sage. Musonius divides the types of trainings into two categories, those which affect the body and soul together, and those which only train the soul.

“Since it so happens that the human being is not soul alone, nor body alone, but a kind of synthesis of the two, the person in training must take care of both, the better part, the soul, more zealously; as is fitting, but also of the other, if he shall not be found lacking in any part that constitutes man.” — Musonius, Lecture 6.4

The reasoning for these types of training is the cosmological view of the Stoics, and their physics. Within Stoicism, anything which acts or can be acted upon, extends in three dimensions, and offers resistance, is a body. Soul, then, must also be a body of some sort.

We get an example through Chryssipus of how this may be. In a crowded marketplace, the voices of many shouting people are all impressed upon the air (as sound waves), and the air holds many impressions at once. The stuffs of which the soul is made is similar. It is not like a wax seal, which can only take gross features, and only one a time, but a very “fine textured” thing which holds many impressions. This ‘stuff’ is of course pneumatic.

In Stoic physics, bodies in the cosmos have differing levels of ‘pneumatic tension’ or τόνος. This is represented in various ways, in a complicated schema that explains everything from stones, to raccoons, to the rational soul of human beings. This high tension of πνεῦμα (pneuma) in man’s rational soul is caused by the fire from the animal-nature of the body, and the air from the god-nature of the pneuma.[7] This is a very simplified version of Stoic physics, and if you’ll permit me to mostly gloss over the details, the purpose of this short explanation is to show the Stoic explanation for just how men are related to the Gods: by nature of pneuma and our propensity for virtue.

Musonius and the City of God

“Well, then, you must not consider it really being banished from your fatherland if you go from where you were born and reared, but only being exiled from a certain city, that is if you claim to be a reasonable person. For such a man does not value or despise any place as the cause of his happiness or unhappiness, but he makes the whole matter depend upon himself and considers himself a citizen of the city of God which is made up of men and gods.” — Musonius, Lecture 9.2

It is commonly accepted that the Stoics recognized two polities, that of man and that of God.[8] As heritage from our Cynic forebears, the idea that all rational creatures are citizens in one universal city-state presages the coming Christian understanding of the Kingdom of God. We see this in Musonius’ own time as well in a Lecture on exile, and how we may be removed from one spot of earth, but we have still people, resources, the stars, and the kinship of the divine.

Humans, then, can never really be exiled, they merely can be removed from one plot of land to another. Musonius experienced exile twice in his life, and Epictetus after him went from Rome to Nicopolis where he set up his own school. In this we see a theological answer to a political question. No matter what happens in the polis of men, our citizenship in the City of God maintains that we are at home everywhere. A reassuring thought, maybe, for those of us far away from our familial places.

“In general, of all creatures on earth man alone resembles God and has the same virtues that He has, since we can imagine nothing even in the gods better than prudence, justice, courage, and temperance. Therefore, as God, through the possession of these virtues, is unconquered by pleasure or greed, is superior to desire, envy, and jealousy; is high-minded, beneficent, and kindly (for such is our conception of God), so also man in the image of Him, when living in accord with nature, should be thought of as being like Him, and being like Him, being enviable, and being enviable, he would forthwith be happy, for we envy none but the happy. Indeed it is not impossible for man to be such, for certainly when we encounter men whom we call godly and godlike, we do not have to imagine that these virtues came from elsewhere than from man’s own nature.” — Musonius, Lecture 17.2

Man’s citizenship in that divine city is a matter of birthright:

“In general it is of the greatest importance for the good king to be faultless and perfect in word and action, if, indeed, he is to be a “living law” as he seemed to the ancients, effecting good government and harmony, suppressing lawlessness and dissension, a true imitator of Zeus and, like him, father of his people.” — Musonius, Lecture 8.10

For Musonius, the City of God is paralleled in micro-form in the cities of men. The functions of the magistrates and the courts are in the same manner ‘natural’ as the Logos and pneuma which orders and regulates the universe. Much of his Lectures, when trying to argue for the existing social norms and mores are couched in arguments from authority. The assumption is that the lawgivers are fulfilling a natural and pious function of the cosmos.

“How, then, can we avoid doing wrong and breaking the law if we do the opposite of the wish of the lawgivers, godlike men and dear to the gods, whom it is considered good and advantageous to follow:” — Musonius, Lecture 15.2

For me personally, the hardest thing to accept in Musonius is the seemingly religious duty to obey the lawgivers. Musonius discusses in Lecture 10 whether a philosopher will prosecute someone for personal injury. His answer is “no,” she won’t. However, we recall the charges Musonius himself brought and testified to of Celer, does this present a conflict? Celer was a fellow Stoic, no less, let us keep in mind.

No. Musonius’ suggestions that a philosopher avoid suits of personal injury is well-grounded in Stoicism, but so too is his participation in Celer’s trial. Musonius was seeking justice to a man betrayed. Justice, being one of the four constituent parts of Virtue; his endeavor was thus in accord with his own teaching.

It seems that we can infer a difference in his thinking between the personal injury claims of civil or equity law; and the laws of the state (malum in se if not malum prohibitum) and criminal law.

Granted, this is an interpretation between what we have of his teaching and the way he lived his life. We have it from our sources that The Roman Socrates was especially known for practicing what he preached. It is reasonable, then, I think, to infer this dichotomy between the civil and criminal law.[9]

The portion of the above reasoning I neglected previously, is that malum in se can be viewed through lens of ‘universal or cosmic’ wrong. It’s something against the natural order of the universe. Basically, it’s a sin, as a Stoic would recognize such a thing.

Malum prohibitum is solely the laws of men, which may or may not be corrupt, vicious, or otherwise not in line with the natural law of the universe. As such, those second types of law should have no moral binding on a Stoic, merely the first: the laws of God.

Conclusion

Musonius Rufus as the least-studied Stoic also has some of the smallest reserves of works which have survived. Since he himself wrote nothing, we have only the surviving fragments of his students Lucius and Epictetus to go on.

Yet, even in those incomplete pieces, we see the hints and clues of a large and gestalt system of Stoic thought which covered all the wide ranges and avenues of life. Indeed, Musonius’ teachings carry a specificity which is lacking in every other surviving Stoic work. He covers every little thing from food, to clothes, to marital obligations, the role of women in philosophy, lawsuits, to home furnishings.

It is through the explicit practice of daily life that we can see “philosophy as a way of life” in the way it could have actually been lived. With practice ever in action, and thoughts of God and piety ever on the mind; the practicing Stoic as Musonius or Epictetus would have known it, would certainly be a thing to behold.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Rufus, C. M., & Lutz, C. E. (1947). Musonius Rufus, “the Roman Socrates” New Haven: Yale University Press.

[2] Dillon, J. T. (2004). Musonius Rufus and education in the good life: A model of teaching and living virtue. Dallas: University Press of America. pp. 52-54

[3] Laertius, D., & Yonge, C. D. (1853). The lives and opinions of eminent philosophers. London: H.G. Bohn. 7.138

[4] Algra, K. (2003). Chapter 6: Stoic Theology (B. Inwood, Ed.). In The Cambridge companion to the Stoics (pp. 165-166). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. Subsection IV.

[5] Valantasis, R. (2001). Musonius Rufus and Roman Ascetical Theory. Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/2201/5953

[6] Rufus, G. M., & Hense, O. (1905). C. Musonii Rufi reliquiae. Lipsiae: Teubner. Chapter XV

[7] Graver, M. (2007). Stoicism & emotion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[8] Sellars, J. (2007). Stoic Cosmopolitanism and Zeno’s Republic. Retrieved January 30, 2016, from https://www.academia.edu/1038467/Stoic_Cosmopolitanism_and_Zenos_Republic

[9] Patrick, K. L., Jr. (2015, October 21). On Musonius Rufus and law suits. Retrieved January 30, 2016, from https://mountainstoic.wordpress.com/2015/10/21/on-musonius-rufus-and-law-suits/